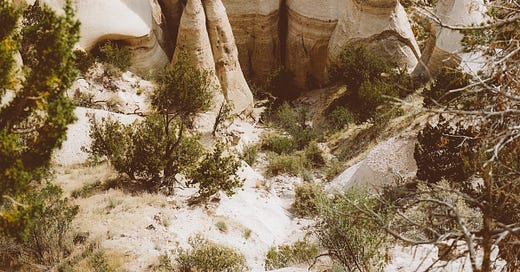

PHOTO BY AERAN SQUIRES

As the publishing branch of the Weaving Earth Center for Relational Education, Loam is continually humbled to be a part of the WE ecosystem (you can learn more about our work together here). We always learn something new, brave, and beautiful from the Weaving Earth crew!

Last year, we were excited to invite Sam Edmondson and Lauren Hage of Weaving Earth to contribute to our Questions for Resilient Future Series. Curated in collaboration with the Center for Humans & Nature, this series is an exploration of disposability culture and community care (for more context, check out this conversation between Loam co-editors Kailea Loften and Kate Weiner and CHN Managing Editor Katherine Kassouf Cummings or this recent post).

Below, you’ll find an excerpt by Lauren and Sam from our anthology “How Do We Come Together in a Changing World?”. We hope that their embodied prayer for practicing ‘no away’ living’ can be a “counterspell to the manacles of modern life.”

A last note: we have extended the pre-order period for this publication to June 1st. We’re so grateful to those of you have already supported us, and if you are a library, community organization, or group seeking several copies—reach out to us!

[YOU CAN’T COME IN]

I heard raised voices.

“What’s happening over here?” I asked with concern. Two six-year-olds were near tears.

“They won’t let us play with them,” they said, pointing at another pair of six-year-olds who were standing by a bay tree.

“Well, this is our house,” one of the kids from the second pair explained back.

“And why can’t they come into your house?” I asked.

“Because we’re playing private property and this is our house.”

I’ve spent a lot of time with little ones, and never had I heard them use that phrase before. Playing private property.

“Where did you learn to play that game,” I asked?

“Well, there’s private property all over my street,” one said.

“Ya and they can’t come in! These are our weapons to keep them out.” They held up sticks as pretend weapons to protect their home.

“Oh yeah?!?” replied the first pair. “Well, we’re playing private property too and this is our house and no one can come in.” And off they went looking for weapons of their own.

[LESSONS LEARNED]

The interactions in this story were witnessed by Lauren, Weaving Earth’s Executive Director, in the early weeks of a youth program. Weaving Earth Center for Relational Education provides nature-based education for action at the confluence of ecological, social, and personal systems change. Our curriculum weaves Earth intimacy, co-liberation, embodiment, and prayerful action into programs for adults, teens, youth and organizations. This short story is a stark reminder that training in the rules of society starts early. Present within it are so many themes that impact daily life:

Privatization of place. Ownership of the Earth.

Consequences for those who cross the line.

Violence.

Trauma.

And embedded within it all:

Who belongs and who doesn’t.

and therefore…

Who matters and who doesn’t.

[HURT BACK]

“We live in a disposability culture—a society based on consumption, fear, and destruction—where we’re taught that the only way to respond when people hurt us is to hurt them back or get rid of them,” writes Kai Cheng Thom.1

In the opening story, the youth who weren’t allowed in found walls and weapons of their own. To hurt back. We don’t blame them—human history is rife with examples of walls, weapons, violence, and vengeance. Today’s world teaches these topics in so many ways. But we also needn’t abandon our youth to that cycle. There are other possibilities.

Humans have a range of relational capacities, from generosity to greed, from pacifism to horrific violence. Culture dictates which capacities prevail. That doesn’t mean that a peaceful culture is free from violence—rather, the presence of violence is due to individual aberrations rather than collective impulses or institutional processes, and it deals with violence in restorative rather than punitive ways. In the reverse, peace is the aberration. Which type of culture is ours?

[SUPREMACY]

Disposability culture is kin to what we at Weaving Earth call supremacy culture.

Supremacy culture is made up of ideologies that elevate one group over another—humans over “nature,” rich over poor, white people over people of color, for example. These ideologies are entangled with institutional policies and actions that extract resources, labor, freedom, dignity, and so much more from the arbitrary out-group(s)—those who do not “belong,” those who must be “managed”—to fortify the position of the arbitrary in-group—those who “belong,” those who “deserve power.”

In simple terms, ideologies are a collection of stories, assembled into beliefs that describe what is or isn’t true about the world.

What do you believe is true about the world?

What stories have you watched, read, heard, or experienced that support your beliefs?

Stories are integral to how humans navigate the world. Some say that story and storytelling is —perhaps the—defining feature of the human experience, particularly our success as a species.

Because the world, let alone the universe, is far too complex and mysterious to comprehend fully, ideologies and the stories that support them are useful: They fill in our extensive and inevitable gaps of knowledge with broad brush strokes. They connect us to people we’ve never met. They are often a shorthand (and stand-in) for direct experience.

But they can also be problematic and harmful. For example, within supremacy systems, prejudiced stories are employed to rationalize why an out-group is in a disadvantaged position—it inevitably boils down to some explanation of their inferiority, not because the system is rigged.

Spoiler alert: the system is rigged. In fact, we live in a series of interlocking systems that are harmful by design.

Here’s one of far too many examples: White supremacy is present and pervasive in all facets of US institutional life. It systematically prioritizes white wellness at the expense of other racial groups, relying on long-standing and ever-evolving racist stories to explain away the very real and very consequential differences in everything from life expectancy to infant and maternal mortality, from wealth accumulation to rates of state-sanctioned murder by police.

We have to resist such stories.

What does our resistance look like? Education—in family, school, and media systems—is how we learn the stories that shape the way we interpret the world and how we show up in our relationships. If we want to change those stories, education is an essential intervention.

We believe education today must critically engage inherited stories of separation and domination, and, at the same time, responsibly recollect a deeper human inheritance: stories of interrelationship, belonging, dignity, and respect.

This is the goal of our Relational Education programs. When we navigate the world with different stories, it fundamentally changes how we show up in our relationships.

[DISPOSABILITY]

Humans are a social species and yet, in many societies, people seem to be failing catastrophically at cultivating and maintaining healthy relationships of all kinds—to ourselves, to each other, to our stuff, to the truth, to the sources of our sustenance, to the Earth.

Deep, satisfying relationships aren’t easy—they take considerable time and effort to flourish. They require energy that is s l o w and s u s t a i n e d.

The United States—our national frame of reference—seems driven by opposite forces. Life is fast and fickle. We aren’t encouraged by the mainstream to tend, mend, or to move slowly. Rather, we are trained by social and digital algorithms to end and move on, quickly. Toss, swipe, scroll, ghost. Get what’s new. Be what’s new. If you don’t like this feeling or this friend, change the channel. Find a new distraction.

The demands of daily life leave many of us lost in a fog of hustling through our daily patterns to make ends meet. Too rarely do we get glimpses of a bigger reality—beyond ourselves, our lists, our jobs, and our strivings for a bigger piece. This narrow frame is like a spell, cast by the unceasing demands on our time, energy, and attention.

Which brings us back to Kai Cheng Thom’s quote and a word they used to describe the dynamics of the day:

disposability

Disposability is one of the most serious generational problems we face today. It originates in human supremacy—the false notion that humans are better than, wiser than, and therefore separate from, the rest of nature. Systems that abide by human supremacy find little use for “nature” beyond what can be extracted for profit. Therein lies nature’s value—it is money, never the sanctity of a river or the dignity of an elephant or the beauty of an old-growth forest. This losing logic is at the root of the ecological crisis we face today.

Something disposable can be used up and “thrown away.” Once spent, it no longer has value—maybe it never really did in the eye of the beholder. And while human beings have been making value judgments for millennia, today is dramatically different, precisely because we live in a world of single-use plastic and planned obsolescence, where the new thing I buy is practically obsolete at the moment I buy it and most of what it came in is instantly discardable. This is a world where someone asks if I want a plastic bag for my plastic bag of chips.

Disposing of things is a daily ritual for many, as quotidian as breathing. As a direct consequence, there is a small continent of plastic in the Pacific Ocean. Landfills are nearing capacity. Climate change is raging.

This lifestyle of “throwaway living” is only a few generations old, but the consequences go far beyond pollution. Research from the University of Kansas “found a correlation between the way you look at objects and perceive your relationships.” The author of the study said: “Even in romantic relationships, when I ask my students what would they do when things get difficult, most of them say they would move on rather than try to work things out, or God forbid, turn to a counselor.”2

In other words, the prevalence of disposable objects in our lives is causing our interpersonal relationships to suffer even more than they already were.

Take the supremacy systems that shape our lives and imbue them with the psychological impacts of throwing things away. Again. And again. And again.

Countless times every day, we make decisions about what has value and what doesn’t, and that extends to people, places, and even possibilities for the future.

[THROWAWAY LIVING]

On August 1, 1955, LIFE magazine published an article called “Throwaway Living: Disposable Items Cut Down Household Chores.” We can imagine how revelatory this article might have been for some who read it at the time.

After the economic and military upheavals of the previous decades, the 1950s seemed hellbent on reasserting normalcy—for white men, at least. Social and political conditions for marginalized members of US society were oppressive. For example, Black families were still contending with a racist, segregated society that wasn’t changed by the service, sacrifice, and loyalty demonstrated through the war.

Many white women were relegated to the high-pressure, high-labor, no-wage role of housewife. With all of housewifery’s attendant expectations, the ease of disposable items was undoubtedly attractive. The LIFE article was accompanied by a photograph of a young, white family of three, all smiling with their arms in the air. They are standing around a trash can, with disposable items of all types floating around them.

Presumably, the trash is floating because they’ve literally tossed it away and up into the air. Their raised arms also signal a rejoicing in the convenience of modern life.

The article begins: “The objects floating through the air in this picture would take forty hours to clean—except that no housewife need bother. They are all meant to be thrown away after use.”

Among the listed items (juxtaposed by us with their landfill lifespans) were:

paper cups (20 years)

foil pans (400 years)

disposable diapers (500 years)

We aren’t blaming white housewives for the mess we’re in. The real problem is that there is no away.

[THE MYTH OF AWAY]

Away =

a local landfill that is nearing capacity, or

the Pacific Garbage Patch, or

an incinerator, which causes severe health problems in the fenceline neighborhood where it’s located, the residents of which, in general, are disproportionately Black and brown families.

Away is relative, never absolute. Away is always some other being’s here. We live on an interconnected planet—“away” doesn’t actually exist.

“Away” probably became a place (conceptually) when ecosystem people became biosphere people, to use Raymond Dasmann’s popular analysis.3 In short, ecosystem people live entirely off the “resources” of their local ecosystem. Biosphere people, however, use (and come to depend) on “resources” from elsewhere, often with little to no care about the places or the peoples from which “resources” are taken. This is colonization. This is extractivism. This is where exploitation of entire peoples and places comes from.

The US is a biosphere society, and for all of the stories of US exceptionality, we’ve wreaked havoc on the world, US residents very much included. It isn’t generosity, integrity, or thrift that made us master—it’s sharp teeth and commitment to a losing logic: if we don’t plunder the Earth, someone else will.

The problem is that what we and others have plundered—“resources”—are more accurately described as kin. We are related. We share interconnected realities. These “resources” are beings, just like us humans, with spirit, stories, and languages of their own. We can learn to listen to them.

Can “away” actually exist if we embrace this level of relational intimacy?

Can the systems that enable disposability withstand an interruption of the unspoken contract (imposed on us through supremacy legacies) that we are separate from—and more important than—the rest of the planet?

[LEGACY]

Today, you can make a choice that will impact the Earth 1 million years from now. It’s quite easy, actually. All you have to do is put a glass bottle in the trash. Forty thousand generations from now, it will still be here.

Trashed plastic bottles will be around in eighteen generations; soda cans in eight.

We wish we could confidently say the same for our descendants.

That’s dramatic, yes, but it’s also the painful truth—the latest UN Climate Report is the most sobering warning yet on the perils of our current path.4

We are what we practice, and what we practice in the present determines our future. The youth playing private property didn’t invent that game out of nothing. They saw adults practicing it all around them and they followed suit.

What will we practice?

What would it take to practice living in a way where no thing and no body was disposable?

What would it take to practice living with love instead of fear?

What would it take to practice living with new stories and believing in new possibilities?

What if the lives of our children’s children’s children depended, at least in part, on the love we kindled in this life for the rivers, forests, mountains, clouds, and creatures that unfold among us?

The work ahead is big, but it is facilitated by the steady rhythm of our daily practice. And before you succumb to some hopeless story that says this is just the way it is, we offer a counterspell to the manacles of modern life, from our twenty-eight organizational values:

Humans Are Capable of Living Beyond Dominance

The systems of dominance that shape our lives will ultimately fall.

How do we ensure they won’t be replaced by new supremacy systems?

We can study historic/current injustices, practice in the present, and perhaps most importantly, summon the skill to imagine a future in which dominance doesn’t define how we relate to one another and the Earth.

Imagination, humility, and action are the gait of our movement.

Thom, K. C. (2020, August 13). 8 steps toward building indispensability (instead of disposability) culture. Everyday Feminism. https://everydayfeminism.com/2016/11/indispensability-vs-disposability-culture/

Sorrel, C. (2016, February 25). Our disposable culture means we toss relationships as quickly as we … Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/3057089/our-disposable-culture-means-we-toss-relationships-as-quickly-as-we-throw-away-objects

Dasmann, R. (2003). 16. Ecosystem and Biosphere People. In Called by the Wild: The Autobiography of a Conservationist (pp. 152-161). Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520927407-019

Kaplan, S. (2023, March 20). World is on brink of catastrophic warming, u.n. climate change report says. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/03/20/climate-change-ipcc-report-15/.